HUOT

I first became acquainted with Robert Huot in the late 1970s, while doing research for a book on avant-garde film. I learned that he was living in central New York State, not far, as it turned out, from where I lived, near Utica. I made arrangements for a visit, and a private screening, and found my way to Huot’s farm near New Berlin. Huot himself had great physical presence and considerable charm, and as he showed me around his big, old, three-story farmhouse, I was surprised to realize that he was clearly a mature painter with a long enough history to have worked through several productive phases. I was to learn more about his painting and his other art activities as the years went by, but on this afternoon, the focus was one of the 16mm diary films Huot had been making since 1970. I don’t know what I expected to see; I was just following a lead that I assumed wouldn’t take me very far, cinematically at least. But what I discovered was film unlike any I’d seen to that point, an aggressively personal film shot with formal rigor and elegance and organized into an ingenious structure.

I asked Huot if he had other films, and at the end of the afternoon, he sent me home with a pile of them. That night, in my office/screening room, I projected Rolls: 1971 and was astonished, as Huot’s sense of timing and ingenious compositions seemed to transform my space into his. Huot’s first diary films – One Year 1970 (1971), Rolls: 1971 (1972), and Third One-Year Movie- 1972 (1973)- remain landmark contributions, not merely to the avant-garde genre of the diary film but to modern independent cinema.¹

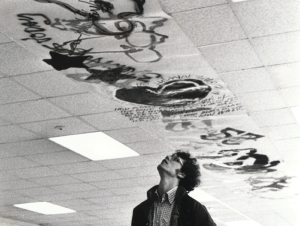

Robert Huot – From One Year 1970

In the years following my first meeting with Huot, I took the opportunity to explore the work he had done before he began as a film-diarist, and I’ve done my best to keep up with the work he’s done since. It’s become clear to me that Huot’s productive filmmaking years slowed, and in the 1990’s he returned to painting with renewed excitement.

Huot’s involvement with painting began in the mid-1950s, when he was a student (and chemistry major) at Wagner College on Staten Island. As result of the influence of Wagner teacher/artist, Tom Young, Huot, still a teenager, found his way to the Cedar Bar on University Place off 8th Street in New York, where a vital art scene had developed around abstract expressionism. Huot hung out with Franz Kline and other important artists. After graduation from Wagner, and two-year stint in the army (1958-1960), Huot moved into Manhattan, where he supported himself by working as a pigment chemist and studied for a time at Hunter College with Fritz Bultman and George Sugarman. By 1964, he had several significant one-man shows, first at Stephan Radich Gallery and subsequently at Paula Cooper, as well as in West Germany and Switzerland.

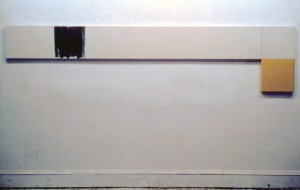

During the 1960s, Huot’s art practice underwent continual evolution. Beginning as an abstract expressionist (from 1956-1961), Huot soon began to react “to the idiosyncratic gestures of our art fathers.” ² By the mid 1960s, he was questioning the conventional shape of painting in a variety of rigorously formal ways. For the Spring Line series, e.g., Huot used the module of the square to structure paintings that stretch into long, narrow, horizontal, subtly-balanced two- and three-part canvases-premonitions of his later work with 16mm filmstrip. His work became increasingly minimal until, at the end of the decade, political concerns-a revulsion to the Vietnam War in particular, and accumulating doubts about the way art-making functioned in society – led to his involvement with the

Two Blue Walls

Sanded Floor Coated with Polyurethane

March-April 1969

Paula Cooper Gallery

Art Workers Coalition and to conceptual pieces that abjured the discreet, saleable artwork altogether.³ Working with strips of tape, slightly modifying architectural details in the living spaces of friends, making sand paintings at night and sweeping them up before anyone saw them, painting two walls of the Paula Cooper gallery blue and coating the sanded floor with polyurethane, Huot searched for ways to work as an artist without participating in the commerce of art, which seemed to continue oblivious of larger political developments. Finally, Huot’s interest in making art that was virtually invisible led to his own disappearing act: he bought a farm in central New York and, with his spouse, Twyla Tharp, moved into the farmhouse to reconnoiter.

Robert Huot and Hollis Frampton – 1972

The rhythms of the farm forced Huot out of his city sense of time and into new ways of thinking about art. In 1965, Huot met Hollis Frampton whose interest in film and willingness to share what he knew with Huot, helped him later enter the arena of filmmaking.4 During the late 1960s, Huot successfully brought his minimalist/conceptual aesthetic to celluloid, with inventive results: he scratched into the emulsion (for Scratch, 1967), spray painted strips of clear leader (for Spray, 1967), embedded a single frame of photographed imagery – a close-up of a woman’s crotch – within several minutes of monochrome red (Red Stockings, 1969); against a black background, recorded a nude white woman slowly covering herself with black paint (Black and White Film, 1969), and paid homage to Duchamp (Nude Descending the Stairs, 1970). At the farm, however, Huot’s filmmaking and his painting took a different turn. Far from the requirement of performing for the New York City art world, Huot began to perform for himself, in order to clarify who he was. If his performance Wall, presented in 1968 at the Angry Arts Festival where “Having placed a white wall on stage, he demonstrated its strength by having a performer fling a hard rubber ball at it. Suddenly, a burly figure (Huot) burst through the wall [toward the audience] in a physical demonstration of the power of determination”, represents the volatile, super-energized Huot of the 1960s, the opening of Third One-Year Diary-1972, where we see Huot taking a shower in a long, slow, continuous shot epitomizes the new, more vulnerable, more serene Huot of the 1970s, candidly exposing the day-to-day realities of his life, washing away the past, beginning anew.

Robert Huot – Diary Paintings

For a time, Huot worked back and forth between diary filmmaking and diary painting: an extensive series of paintings made, for the most part, on rolls of canvas.6 On a given day, a section of canvas a few feet long would be exposed, Huot would paint on it, and when the paint was dry, he would roll up the canvas, and expose a fresh section. The results were generally eight feet wide and often sixty feet and sometimes ninety feet long. In both the diary paintings and the diary films, Huot explored what each new day might bring: it might be a portrait, an exploration of the formal properties of paint or film stock, a bit of graffiti referring to his chores on the farm (“mowed some more”.) Once he reached the end of the roll of canvas, or had exposed his final roll of film for the year, he would discover the structure that (in the paintings) had accumulated, or (in the films) seemed demanded by what he had recorded. In both painting and film, accidents, mistakes, “failures” were included as part of the finished work – a gesture of openness about the artistic process that complemented Huot’s new openness about himself.

By the end of the decade, Huot had become interested in Super-8 film because the narrower gauge was far less expensive to work with than 16mm, and therefore a more democratic, popular media-making alternative, also offering the opportunity for working with sound. Beginning in1978, Huot’s diaristic impulse was channeled into elaborate Super-8 features that revealed considerable dexterity with the new medium. If Super-8 film never achieved the widespread recognition that at first seemed likely (as a result of a combination of factors: most obviously the refusal of exhibitors to equip theaters with the first-rate Super-8 projection, and later, the advent of accessible synch-sound video technology), Huot’s Super-8 work from 1978 into the 1990s, and specifically Super-8 Diary: 1979 (1980), Diary 1980 (1982), 1983 Diary for five projectors (1984), and Dark the Dominatrix (1995) – stand with the best American narrow-gauge work of the era.

The Super-8 diaries, like the earlier diary paintings and films, also provide a context for Huot’s other art activities, including his collaboration with Twyla Tharp in Deuce Coupe (1980, music by the Beach Boys), a series of anti-nuclear posters he designed for exhibition in New York subway stations, and in one instance, as a fund raiser for Peter Watkins’s epic, transnational mass-media critique, The Journey (1987); and a fascination with the equilateral triangle that, in the 1990s, has drawn him back into painting.

In the beginning, Huot’s interest in the triangle seemed a function of the synergic implications of the form, utilized in R. Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic dome. But the triangle allowed Huot to combine several concerns that have been characteristic of his work since the 1960s. In addition to providing a dynamic frame within which he can –re-explore painting, the equilateral triangle provides a module – like the square in the Spring Line paintings, the film frame, the daily space on the rolls of diary paintings – that makes each new painting part of a series, an extension of what’s gone before, an entry in an implicit diary of artistic investigation.And because the triangle paintings are potential modules, when they are grouped in a show, as they are here, they re-form the gallery space into an environment that feels as much like Huot’s own as my home screening space became as I watched, in amazement, those first 16mm diaries.

Scott MacDonald

Professor Emeritus

Utica College of Syracuse University

1 The form of the film diary is usually credited to Jonas Mekas: see David E. James, “Film Diary/Diary Film: Practice and Product in Walden[Mekas’s Walden],” in James, ed., To Free the Cinema (Princeton University Press, 1992), pp.145-179. I discuss Huot’s early diaries in “Surprise! The films of Robert Huot: 1967 to 1972,” Quarterly Review of Film Studies, Vol. 5, No. 3 (Summer 1980), pp. 297-318. Huot and I discuss these films at some length in our interview, which is included in A Critical Cinema(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988), pp. 90-115.

2 Huot, in brief catalogue essay for the Allianz 8 Gallery in Stuttgart, Germany in 1980.

3 Several Huot pieces are discussed in Lucy Lippard’s history of conceptual art, Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art object from 1966 to 1972 (London: Studio Vista, 1973).

4 The relationship between Huot and Frampton has never been adequately appreciated.

Certainly the relationship involved more than Frampton’s teaching Huot the basics. Frampton’s Manual of Arms (1966) includes a portrait of Huot, who also appears in Frampton’s Artificial Light (1969). Frampton’s Lemon (1969) is dedicated to Huot, whose farm is the location for the final section of Zorns Lemma (1970), during which Huot is a member of a threesome – man, woman, dog – who walk across his pasture to the woods in the distance (Frampton also alludes to Huot’s Two Blue Walls…, in the central section of Zorns Lemma: Huot painting a wall is a recurring image). Frampton appears a number of times in One Year (1970) and in Third One-Year Movie – 1972, and was cameraperson on Black and White Movie and Nude Descending the stairs.

5 Don McDonagh, The Rise and Fall of Modern Dance (New York: Outerbridge & Dienstfrey, 1970), pp. 310-311.

6 Lucy Lippard, Eunice Lipton, and Don McDonagh discuss the diary paintings in the catalogue for Huot’s diary show at the University Art Gallery at S.U.N.Y.-Albany in 1976.