THE FILMS OF ROBERT HUOT: 1967 to 1972

In a decade when tens of thousands of men and women throughout the world are independently producing films in 8 and 16mm, to presume that we already know who the most inventive, most exciting contemporary filmmakers are is extremely foolish. Of course, impressive bodies of work have surfaced, and we may feel confident that future developments will in no way eclipse them. Nevertheless, because so few regular screening opportunities for independent film have developed and because, by and large, the few journals which cover independent film to any degree have tended to publish pieces on filmmakers who are already comparatively well known, it has been difficult, and continues to be difficult, for filmmakers who do not carefully maintain their public relations to be recognized at all. The problem is exacerbated by the fact that if a major genre of film is developing in the 1970s – as psychodrama developed in the 1940s and formal film in the 1960s – it is probably diary film or a variety of combinations of diary and formal film; and the makers of diary films can be predicted to be a good deal more private about their accomplishments than filmmakers involved in less personally revealing types of work. This may seem to be proved by a single look at the almost entirely unknown body of work produced since 1967 by a completely unsung filmmaker named Robert Huot; in my view, it constitutes one of the most impressive achievements of the American independent film movement.

For the purposes of this discussion, Huot’s films can be divided into two groups: the small group of short films he made in 1967, 1968, and 1969; and the sizeable body of diary work which has dominated his filmmaking since 1970. By the late1960s Huot was becoming a widely recognized painter; until he became disillusioned with the New York scene and dropped out, his conceptual and minimal paintings were regularly exhibited alongside works by Frank Stella, Larry Poons, and Sol LeWitt. The earliest films reflect his interest in applying the concerns he was then exploring in his painting to a new art form. They are also evidence that from the beginning Huot was committed to an informal kind of filmmaking, which at first resulted in his making films with whatever materials and methods happened to be handy.

Leader and Scratch are extensions of Huot’s early interest in minimalism. Both may reflect a desire on his part to “out-minimalize” other film artists, but they are successful in reducing the number of filmic variables so completely that essential qualities and potentials of the materials of film can be felt. While Scratch is nothing more than eleven minutes of dark leader with a continuous handmade scratch, the resulting imagery varies a good deal, depending on how deeply Huot dug into the emulsion: when the scratch is shallow, for example, it seems to bead and move up through the image; when the scratch is deep, it seems to remain within the frame, vibrating horizontally. Leader is a bit less extreme that Scratch. Framed within beginning and ending passages of academy leader, strips of black, green, and clear leader alternate, at first every thirty seconds, then more and more quickly, and finally much more slowly. These irregular alternations intensify our awareness of some of the potential variations in the direction and mode of our attention during a screening. When green leader is projected, continual shifts in color density tend to keep the eye attentive to the screen. During passages of black leader, on the other hand, the screen is so dark that it provides almost nothing to look at; as a result, one’s attention tends to be drawn to other light sources, especially to the projector, if it is within the screening space. When clear leader is projected, we are aware both of the tiny events occurring on the screen and the lighted screening space.

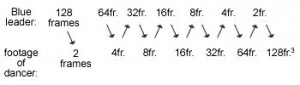

By 1968, Huot had begun to use photographic imagery, fusing his continuing concern with until I located the frame and discovered an image of a naked female crotch. The title clarifies the erotic joke, which, however, exists only if the viewer is willing to examine the film closely enough to be sure of what is there. In Cross-Cut-A Blue Movie, Huot presents a minimal passage of intercutting between found footage of a hoochy-coochy dancer and a blue leader, organized as a pair of inversely related geometric progressions: minimalism and an interest in the erotic. Red Stockings is a demonstration of the power of a single frame of photographic imagery. Except for one frame, the entire three-minute film is a continuous, uniform red which creates a variety of afterimages and other optical illusions. When the lone frame flashes by halfway through the film, the imagery is difficult to identify, but it has a somewhat erotic quality which, when I first saw the film, sent me to the rewind. I scanned the red

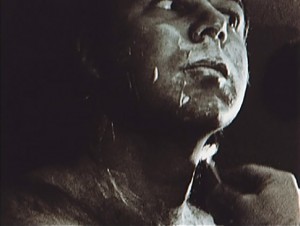

The resulting film is amusing (because of the pun in the title, the speed of the editing, and the funny fast-motion shimmy of the dancer); highly rhythmic (both because of the intercutting itself, and because of the rhythms of the dancer’s movements, the flutter of dust particles on the blue leader, and the waver of scratch marks on the footage of the dancer); and formally interesting because of Huot’s creation of the montage which so energetically goes nowhere. For Black and White Film, Huot created his own photographic imagery for the first time. After a few moments of darkness, a young woman (Sheila Raj) lowers a covering of some kind, slowly revealing her naked body. She reaches outside the circle of light, which illuminates only her silvery form, scoops up dark paint, and beginning with her feet, gradually paints her entire body. When she has become invisible except for the faint sheen of the paint, she drops her arms, looks straight ahead, and the film fades to total darkness. The serenity of the film, which is structurally reflected by Huot’s presentation of the action from a single position in a single take, its sensuality, and the aura or ritual it creates (Raj always moves in a formal way and, except when she needs to look for the paint, looks modestly down) make Black and White Film a quietly haunting work.

During the 1970s Huot has continued to make short films. The majority of his filmmaking energy, however, has been channeled into a series of diaries – five have been completed as of this writing – which give evidence of his growing commitment to film and of his considerable creative abilities in the new medium. One Year (1970) was clearly a turning point. While the short early works were interesting films by a painter, One Year (1970) reveals Huot’s sustained attempt to make filmmaking a constant element, if not the central element, of his creative life. One Year (1970) is a series of forty-nine rolls of 16mm film, nearly all of them unedited except in the camera, and all of them silent. The flares at the beginnings and ends of the rolls are not eliminated and, as a result, become a form of visual punctuation. The rolls are arranged so that, as title implies, we move gradually through an entire year, from winter to winter. The most interesting aspect of the overall organization, however, involves the fact that the first quarter of One Year (1970) is very different from the final three-quarters: this change reflects a fundamental alteration in Huot’s approach to film.

The most obvious quality of the first part of One Year (1970) is the care and intensity with which Huot chooses and records his imagery. Of the first nine rolls, eight are gems; had they been released individually in 1970, they would have established Huot as an interesting young filmmaker with concerns and abilities related to those of Larry Gottheim and Barry Gerson. In several instances these early rolls are interesting because of the simple beauty or power or humor of Huot’s imagery. The second roll, for example, records a series of spectacular smokescapes created by a street-level steam vent in lower Manhattan. The fast-swirling smoke in dark, rather ghostly streets creates a mood reminiscent of the German Expressionists. The fourth roll presents six approximately thirty-second shots of the wake of a ship, framed so as to capture the three-dimensional, multidirectional movements of the water within two-dimensional compositions of powerfully conflicting forces. Each shot crates a different composition in which different kinds of forces become evident. Sometimes the collision of different portions of the wake is emphasized; sometimes one is aware of the conflict between the glittering surface of the water and the immense forces welling up underneath. Always, however, one is aware that the powerful imagery one is seeing is a result of Huot’s ability to frame an aspect of everyday reality in such a way as to discover its filmic potential. In the eighth roll Huot captures several black cows in a white winterscape, standing in humorous positions, often miraculously moving in unison as though they’ve been choreographed.

Other rolls in the first section of the film show aspects of film process and equipment. Perhaps the most impressive roll in all of One Year (1970) is the third, in which Huot presents a city intersection filmed from above at consecutively slower speeds. The intersection itself is quite complex; cars and trucks move up and down various one-way streets, people walk along the sidewalks and across the streets, a yellow light on a utility truck a block away whirls around and around, and a window on the second story of a building reflects events occurring outside the film frame. Sometimes events in the foreground capture one’s attention: at other times one tries to decipher events several blocks away. As the intersection is presented at slower speeds, people and vehicles seem to drift through the scene, and the multiplicity of events grows increasingly easy to examine.

At the same time, the texture of the image becomes grainier, the focus softer, the implicit perspective flatter. The result is that while the imagery becomes less difficult to explore in one sense, it grows more ambiguous in another. All in all, the roll is beautiful in its clear demonstration of some of the formal effects of peculiarly filmic elements on filmed imagery.

I can’t resist a brief mention of two other early rolls – the fifth and the ninth – in which Huot continues to explore the interest in minimalism which dominated his earliest films. The fifth presents a single cow enclosed, apparently, by a corral made of posts and wire. After a few moments, the cow suddenly disappears – we realize that Huot has simply stopped shooting, waited for the cow to walk out of the corral and the image, and he continued to shoot – then the viewer is left to mediate for the remainder of the roll on the power and limitations of the film frame, which, like the corral, tends to direct our attention while remaining entirely ineffective in any physical sense. In the ninth roll Huot films a tiny rivulet of cold, clear water trickling over little rapids through a serene winter landscape. His otherwise continuous shooting is regularly interrupted every thirty seconds or so by a tiny flash of light which indicated that the camera has stopped and stared, though no visible change in the imagery occurs as a result. This little roll is effective both as a serialist meditation on a moment and place of natural beauty (the intermission flashes are subtle attention receivers which regularly reconfirm the value of looking at the simple lovely scene) and as a metaphor for the editing process: the flow of the filmed image of the stream is regularly interrupted by Huot’s rudimentary editing, just as the flow of the stream itself is interrupted by the tiny rapids.

By the end of the first dozen rolls of One Year (1970), Huot has demonstrated to the attentive viewer – as he apparently needed to demonstrate to himself – that he was perfectly capable of creating interesting and beautiful films by combining intensity of perception, sensitivity to composition, and judicious use of film technique. During the remaining three-quarters of the film, however, he turns his back on the accomplishments of the early rolls; by dint of will he seems to leave his artistic propensities behind and becomes an amateur.

According to Huot, the reasons for this change dates back to the late 1960s and the conflux of political, economic, social, and aesthetic concerns which led finally to his decision to disassociate himself from the New York City art world and the elitist assumptions about the making and understanding of art which, in his view, were dominating it. Art, he had come to feel, needed to do more than examine its own materials and processes in forms which were accessible only to an in-group of art critics and other artists. In January, 1970, he moved to a small farm in upstate New York and became increasingly committed to creating films and paintings which would more adequately reflect his broadening concerns and which might have a wider appeal. Of course, the differences between the early short films and the first dozen rolls of One Year (1970) are to a degree reflective of his change, but after the first reel (in its present form the film is distributed on four reels with twelve, twelve, thirteen, and twelve rolls, respectively), the change is more radical. The last three reels of One Year (1970) are in large measure a record in Huot’s involvement in renovating the farm, keeping the land productive, and just generally exploring his new terrain. There are rolls of men laying a cement foundation, of a hay field being limed, of people striping and polishing floors, and of the weather, the flora, and the fauna of the farm. Instead of photographing this subject matter with the sophisticated aesthetic detachment which characterizes the early rolls, Huot took the camera off the tripod and filmed as

informally as he could, not worrying about the nuances of exposure and composition. Not surprisingly, many of these rolls are relatively uninteresting for a general audience, but Huot’s decision to relax and let things happen filmically had both the long-term benefits as well: a viewer who remains alert during the final three reels of One Year (1970) can discover interesting visual experiences, some a few seconds long, others lasting entire rolls.

Several of the later rolls deserve special mention. In more than one instance Huot’s new informality with the camera led him to play a kind of visual game, which is recreated when the viewer sees the film. On the tenth roll of the second reel Huot’s camera follows birds that are flying into and out of a field of weeds. Usually the birds fly singly and since Huot is shooting in long shot, they appear as tiny black dots on a grey landscape. What strikes me as fascinating is the speed with which viewers actively involve themselves in the game. After the camera has followed two or three birds, viewers tend to eliminate all other aspects of the image from their consciousness. In those instances when a bird is not clearly visible, one tends to scan the image with some anxiety so that no portion of the game is missed. Other interesting rolls result from Huot’s ability to recognize the potential of accidents and mistakes. The sixth roll of reel 4 presents the meeting of a baby goat and a pet dog. Huot does his best to simply record the funny interaction of the two friendly but nervous animals; the dog tries to play; the goat, much to the dog’s apparent shock, continually tries to mount. At the end of the roll they resolve their meeting, effecting small miracle of composition: the dog walks to the far left of the image, comes forward, and looks directly into the camera as the film flares out and the roll ends. Throughout almost the entirety of the eleventh roll of reel 2, the viewer sees nothing but the dance of black and white film grain and extremely faint modulations which hint at shadowy shapes. Concentration on the grain tends to create optical illusions – color afterimages, etc. – reminiscent of those developed by Tony Conrad in the Flicker and Taka limura in Shutter. Only at the end of the roll, when we see two tiny dots of light in the upper center of the image, do we suspect that the optical experiences were accidentally produced as a result of Huot’s underexposure of some nighttime imagery and that the ghostly images that sometimes seem to inhabit the grain are not optical illusions, but barest imprint of photographic imagery.

By 1971 Huot was in a peculiar situation. He had demonstrated his ability to create effective films by bringing his interests in artistic formalism and minimalism to bear on a new medium, but he had stepped away from that kind of filmmaking, apparently for ideological reasons. And he had proved that he could become completely at ease with the camera as an informal recording device. What is most apparent as one watches One Year (1970) in it entirety, though, is that if many of the rewards of the first reel, like the rewards of the early short films, are available to a relatively small group of rather savvy film lovers, the simple length of the last three reels – the amount of informal personal recording one must go through in order to discover the sudden surprising rewards – limits the appeal of the film even more fully. According to Huot, the length of One Year (1970) is a result of a prior decision to accept the footage he created, rather than to cull from it only that material which looks “artistic,” or “beautiful,” or “professional.” The idea of having a “shooting ratio,” the assumption that filmmakers will waste much of the footage they record, seemed to Huot a filmic reflection of a conspicuously-consuming society which had little respect for its natural or human resources. He was determined to make films which would offer an alternative. The decision to string rolls of film together chronologically in One Year (1970) was a less-than-effective result of this thinking, but during the months following the completion of the first diary, Huot discovered a way of using all the footage he shot, while avoiding the pitfalls of the first diary’s organization. Using editing as a means of taking a dialectic step forward, Huot created Rolls: 1971 and Third One-Year Movie-1972, his two finest films to date.

Rolls: 1971 is so powerful and so unusual in its emotional effects that I find it difficult to discuss. To create this Huot used twenty-two rolls of film shot during 1971, along with bits of other found footage and from materials photographed during the same period. Some of this material is similar to the very best minimal rolls from One Year (1970); other portions are more like the informal later rolls of the earlier film. In addition, he included a good deal of unusually personal imagery (some of it quite sexually explicit), mostly involving himself, Twyla Tharp (she and Huot were married at the time), and their son Jesse. These various kinds of imagery are integrated within a complex and highly suggestive editing strategy which involves the presentation of imagery in two very different ways. In thirteen instances Huot includes complete, unedited rolls – flares and all – just as he did consistently in One Year (1970). Each of these thirteen rolls, however, is preceded and followed by a passage composed of exactly 252 one-second shots taken from both the thirteen rolls including complete and from the other nine rolls and the additional footage. These passages of one-second shots – there are fourteen in all – are organized according to a complex pattern which allows for considerable variety in the kinds of juxtapositions which occur between one-second units. The specifics of the pattern are as follows (the individual numbers refer to the twenty-two original rolls of material used regularly during the film, numbered according to their first appearances; “m’ refers to miscellaneous material culled from other sources):

1 2 3

1 4 5 3 4 2 5

1 6 7 2 6 3 7 4 6 5 7

1 8 9 2 8 3 9 4 8 5 9 6 8 7 9

1 10 11 2 10 3 11 4 10 5 11 6 10 7 11 8 10 9 11

1 12 13 2 12 3 13 4 12 5 13 6 12 7 13 8 12 9 13 10 12 11 13

1 14 15 2 14 3 15 4 14 5 15 6 14 7 15 8 14 9 15 10 14 11 15 12 13 14 13 15

1 16 17 2 16 3 17 4 16 5 17 6 16 7 17 8 16 9 17 10 16 11 17 12 16 13 17 14 16 15 17

1 18 19 2 18 3 19 4 18 5 19 6 18 7 19 8 18 9 19 10 18 11 19 12 18 13 19 14 18 15 19 16 18 17 19

1 20 21 2 20 3 21 4 20 5 21 6 20 7 21 8 20 9 21 10 20 11 21 12 20 13 21 14 20 16 21 16 20 17 21

18 20 19 21

1 22 m 2 22 3 m 4 22 5 m 6 22 7 m 8 22 9 m 10 22 11 m 12 22 13 m 14 22 15 m 16 22 17 m 18 22 19

m 20 22 21 m

This pattern remains the same throughout the film, though the specifics of the juxtapositions vary a good deal because the individual one-second units used during successive repetitions are always taken from positions progressively further into the original rolls. Huot’s complex editing strategy seems calculated actively to involve the viewer in the film to an unusual degree. The passages of one-second shots have a good deal in common with Eisensteinian montage. In many instances, in fact, the formal and thematic differences between consecutive one-second units are at least as diverse as anything in the Odessa Steps sequence.

The first six images of the film, for example, are:

1. A beautiful composed long shot of a heavy snowfall

2. A close-up of Tharp breastfeeding Jesse Huot

3. A medium shot of Tharp spoon feeding Jesse Huot, apparently some months older than in the previous shot.

4. Another long shot of the heavy snowfall

5. An extreme long shot of a windy summer landscape

6. A close-up of Huot beginning to masturbate

The radical disparities between units which are evident here occur regularly throughout each of the one-second passages; in fact, near the ends of these passages, where a single second often contains several bits of very different information, the bombardment is even more intense. The relentless pace of the one-second passages offers a rather bewildering amount of information to viewers (this seems especially the case during a first viewing, before the pattern’s repetitive nature has been established), and the constantly changing collisions of imagery can engage the viewer in a wide range of formal and thematic considerations. The juxtapositions of one-second units, for example, often seem to imply relationships, some of which are complex and multi-leveled (in one instance a shot of a bulldozer plowing a field occurs next to one made by Huot’s scratching directly into dark leader); others rather startling in their potential implications (in at least one instance, the artificial insemination of a cow occurs next to a shot of Tharp nursing Jesse Huot). Sometimes the eye spots a particular aspect of consecutive shots which for a few seconds at least, becomes a motif. I am often aware of an interplay between the various grains of the film stocks and such aspects of the imagery as snowflakes and drops of semen. A more general kind of involvement often occurs once viewers are aware that the one-second units are arranged in a particular pattern and grow interested in determining its specifics. The complexity of the pattern can sustain such curiosity for a considerable time.

While the thirteen unedited rolls, many of which are shot continuously from a single camera position, generally provide “breathers” from the highly edited passages, some of them demand other forms of involvement. The roll of the heavy snowfall (the first complete roll presented in the film) engages the viewer’s eyes in a constant process of adjustment and readjustment between foreground and background; the roll of Tharp nursing Jesse Huot (the second complete roll) is composed so that while viewers know at once what is being presented, a full minute can go by before the entirety of the composition can be seen and understood. Perhaps the most disconcerting complete roll (the fifth) is an explicit close-up of Huot masturbating, which is composed in such a way that even viewers who are bothered by the subject matter and would normally look away tend to become engaged in deciphering the details of what they see; to make the roll, Huot stood straddling the mirror and photographed vertically down his body; the image is framed so that the mystery of the set-up is not solved for some viewers until Huot ejaculates and the semen strikes the surface of the mirror. Other, less formal rolls create other types of involvement: one is amused to discover the accidental rituals surrounding Huot’s and Tharp’s unrolling of a long, long painting (actually the first of Huot’s diary paintings); one follows the unpredictable movements of a group of playful kittens in and out of the image; and so forth.

Still other forms of viewer-involvement are created by the basic alteration of complete rolls and edited passages. For one thing, once the general organization of the film is clear to the viewers, a certain amount of suspense is created by their curiosity about which complete roll will be screened next. This general curiosity is intensified, in some instances, by the desire to have a more complete look at imagery which tends to be mysterious in its one-second appearances and, in other instances, by the fear of a sustained confrontation of personal sexual imagery which remains relatively easy to handle in one-second passages. Secondly, each addition of a new complete roll changes the viewer’s perception of subsequent one-second passages; one grows increasingly familiar with some portions of the passages, more curious about other portions. A third general result is a lesson in the importance of context. I am frequently amazed by the degree to which the identical imagery looks different, depending on whether one sees it explored and understood as in the roll of Tharp nursing Jesse Huot, for instance, I sometimes have trouble deciphering the image in its one-second occurrences. Huot’s heavy involvement of the viewer in Rolls: 1971 is a function of his obvious commitment to communicating the vision which is embodied in the content and organization of the film. The combination of Huot’s amalgamation of two radically different approaches into an almost combative form and his use of this form to present imagery so open and revealing that the decision to use it required a personal vulnerability equal to the film’s formal power results in an extremely untraditional autobiographical work in which unusual sorts or “perspective” are consistently undermined. While Huot’s lack of traditional restraint runs the risk of seeming immodestly self-indulgent to some viewers, it adds a crucial element to the finished film: by developing such an intimate contact between filmmaker and viewer, the most serious sorts of reflection about what a film should be and how it should relate to the viewer’s personal life can hardly be avoided. Rolls: 1971 does more than serve as a general catalyst for viewers’ reconsiderations of their habitual assumptions, however. Specifics of the film suggest fruitful modifications of what many viewers tend to accept as normal. Huot’s decision to use only two kinds of durations – one second, complete roll – creates a leveling effect in which “normal” hierarchical judgments tend to be suspended. Plowing a field, looking at a painting, having sex, looking at a landscape, driving a car, etc. are all seen as integral, important parts of life in which the health of the individuals is determined by their ability to function effectively in the ecological system and to relate fruitfully with one another. Consumerism and the institutional and sociological patterns which thrive on it, particularly those that tend to weaken the dignity of individuals or detach people from fundamental physical needs and desires, are implicitly rejected by being excluded. Specific alternatives are implicit throughout the film. Huot’s presentation of family life and of sexuality are particularly good examples.

While much of Rolls: 1971 is involved in the process of raising a child, one never sees a “family unit” in the usual sense of that term; there is no “head of household,” no housewife. Instead, one sees three individuals. At times they obviously work together, but they also pursue their own interests, and no filmic distinction is made between these; no mystification of family togetherness is developed at the expense of anyone’s individuality. One of the most moving rolls in this regard is the one in which Tharp (a significant figure in contemporary dance) does exercises, apparently getting back into shape after the layoff necessitated by having a baby. For a long time, she seems quite alone – except for Huot, who is respectfully filming her – and then for a second the camera and she move so that one sees the baby playing quite contentedly in the background. In Rolls: 1971 a healthy family is not a group of people, all serving a male, so that the group can be secure and comfortable economically; it is a group of individuals who, for a time, share their interests so that all can grow. Sexuality in Rolls: 1971 is not limited to a “correct place.” Because of the specifics of Huot’s overall organization of the film, the viewer is likely to come across sexual imagery at any moment, and, as a result, grows accustomed to the idea that sexuality – both sexuality between partners and with one’s own body – is simply a natural ongoing part of life, neither more nor less important than the other activities recorded in the film. While Huot’s presentation of sex is quite explicit, it is also clear and matter-of-fact. Sex is presented as a demystified physical activity; there is no attempt to romanticize the hairy particularity of normal adult bodies.

A final important dimension of Huot’s vision in Rolls: 1971 is suggested by elements in the structure of the film which keep it from being entirely predictable. One is the miscellaneous material which is the last addition to the one-second pattern. Even on the first viewing, the viewer quickly realizes that though the overall pattern of one-second shots maybe perfectly regular, the pattern seems to disintegrate at the end as a result of the addition of a considerable range of new material in an undefined order: shots of a film on TV photographed in a mirror; a cow being artificially inseminated; scratches on dark leader, footage of tractors overlaid with color painted directly onto the colloid; color footage of a stripper, etc. Since even the most careful examination of this material reveals no clear organization, one is not surprised to learn that it was selected at random from out-takes which had been thrown into a box during the construction of other films. The structure of the overall film has a similar loose end. During my first viewing of Rolls: 1971 I assumed that it would end as soon as I had seen all the imagery, both in complete-roll form and broken down into one-second units; and I was shocked when the intermittent one-second intervals of darkness which signal the end began to appear in the one-second passage after the thirteenth complete-roll. Huot’s decision to setup repetitive patterns which he ultimately refuses to carry to the conclusion one comes to expect that has interesting thematic implications. The one element which unites nearly all the multifarious imagery presented in Rolls: 1971 is its participation in an ongoing process of growth and creativity: a baby is learning to eat, stand, to know his parents; a man and woman are exploring themselves and each other sexually and aesthetically; the change of seasons is bringing a new cycle of planting and harvest; and the viewer is developing his awareness and sensitivity to all of these processes. By ending the film with nearly all activities still in progress, Huot keeps his structure from implicitly encaging his call for creative evolution; instead of implying a rigid final plan, Rolls: 1971 invites viewers to become involved in the ever ongoing process of making human life more genuine and more fulfilling.

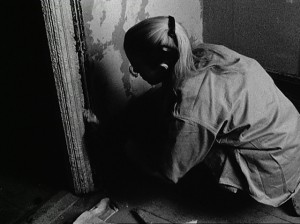

While Rolls: 1971 seems the result of an urgent need to make a film so intimate and so assertive that it cannot fail to send a healthy shiver through the viewer’s complacency, Third One Year Movie – 1972 is mellower and more sensuously beautiful; it seems to reflect an increased commitment to teach by example. As is true in Rolls: 1971, Third One Year Movie – 1972 uses an unusual editing strategy to fuse disparate sorts of imagery into a coherent form. The film includes several lovely single-shot minimal rolls(one amusing roll of cows nudging each other for trough space, framed so that they seem to be fighting to be center screen and photographed with a beautiful clarity; and a magnificent roll of a woman walking dramatically toward the camera through a barn – at first she’s in a cape, but as she approaches, she drops the cape revealing her naked body – photographed in black and white, in slow motion, and with such intense grain that when she nears the camera and looks into it, she appears to be a kind of filmic phantom come to haunt us); informal material of the sort included in the final three-quarters of One Year – 1970 and in Rolls: 1971; various kinds of imagery developed through direct manipulation of film and leader; as well as passages in color negative and superimposition. The image material is organized into twenty-four sections, each separated from the next by a twelve-second passage of academy leader. The individual sections decrease in duration – more or less progressively – from the first and second (which are ten minutes, fifty-three seconds and eight minute, sixteen seconds; and forty-one seconds); the entire film lasts approximately one hour. The many individual units of imagery which make up the sections are arranged so that successive portions of specific rolls are presented, section after section. While the order of the various units is generally predictable, their durations vary consistently and the specifics of the order of image units gradually change as the sections pass. One no sooner grows accustomed to a specific sequence of material that a new element is added, often in a way which makes us wonder whether we are seeing something new or just noticing for the first time a kind of information which has been there in some form all along. In general, viewers tend to search actively for the pattern which informs the imagery, while remaining alert to the fact that this pattern is in a constant process of more or less gradual change.

The overall effect of the editing strategy of Third One Year Movie – 1972 is to reconfirm many of the elements of the vision so powerfully adumbrated in Rolls: 1971, but in a form which is, in some ways, a more accurate reflection of the process of living through a period of time and which more effectively takes account of the variety and evanescence of experience. As is true in the earlier diary, the 1972 film eliminates those aspects of Western commercial culture which implicitly damage individuals’ ability to express and fulfill their physical and spiritual needs, presenting instead a world of individuals living within an environmentally sound, personally accountable context. The passages during which Huot kills, bleeds, and halves a cow are presented in color negative, emphasizing the beauty of being responsible for one’s own needs. The fact that the experience is divided into parts which are included during successive sections suggests both its personal significance and the fact that its practical value and the memories it generated continued throughout the year. Because we can rarely predict exactly what we’ll see at any given point in the film and because of the decreasing durations of the individual sections, we are increasingly confronted with the bittersweet fact that any period of time is of limited duration – and particularly during a pleasant one – the hours, days, years, whatever, always seem to be passing more and more rapidly, and the pleasures they offer seem to require increasing amounts of concentration. As is true in Rolls: 1971, the organization of the many kinds of information included in Third One Year Movie – 1972 does not suggest a finished, perfected experience. Many of the activities are continuing as the film ends. The only specific signal of the conclusion of the film, in fact, is a double repetition of the overall pattern of units, without the usual interruption of academy leader, in the twenty-third section.

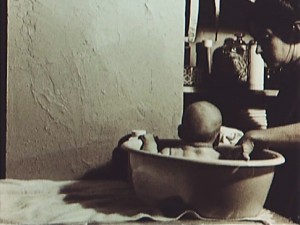

A crucial addition to Huot’s vision involves the consistency with which we are made cognizant of the processes involved in making Third One Year Movie – 1972. The ever-changing pattern of the film’s complex organization, of course keeps us aware of the process of editing; and Huot’s inclusion of a wide variety of imagery developed through direct manipulation of the film and negative raises our consciousness about some of the potentials of basic film materials. In addition, the original act of filming is always an important part of the imagery which is filmed. In many instances people and animals not only look directly at the camera as Huot is shooting, they walk toward him. In some instances this seems sheerly out of curiosity; in the first section, for example, Jesse Huot is playing on some farm equipment, then sees someone filming him (we assume it’s Huot), and toddles smilingly toward the camera to take part in whatever is going on. In other instances, Huot has clearly directed people to walk toward him, as for example, in the previously-mentioned shot during which the woman approaches through the barn. In those parts of the film where Huot is filming himself, he is involved in intimate activities. Soon after the film begins, for example, he presents a nearly complete roll during which we watch him take a shower. At the end of the shot we see him turn the camera off, and during the second section we see the camera come back on just before he walks back into the frame with a towel. In the latter half of the first sixteen sections we see portions of a series of activities involving Huot and a woman in a bathtub (the imagery is framed, incidentally, so that the left edge of the frame is parallel to the floor). At the end of several of the shots which record their interactions – in one instance, immediately after they have sex – Huot reaches out of the tub, finds the remote control switch, and turns the camera off. Perhaps the most consistently obvious instance of this implicit demystification of the process of shooting supplies the image material for the unit which regularly follows the academy leader at the beginning of each section. Huot and a number of students cavort in front of a camera which is held, apparently, by a variety of different people at different times. As we explore this situation, section by section, we realize that Huot’s goal during the class session being filmed is to help his students become more at ease in front of and behind the camera.

By presenting a visual world in which filmmaking is an integral part of nearly every situation, while demystifying the actual process of creation, Huot is able to suggest the importance of art without implying that the excitement and pleasure of making it need be restricted to an elite. Third One Year Movie – 1972 is not presented as a Great Work by an Inspired Artist whose work is a painful ordeal. Instead, Huot presents himself as a man for whom learning to make film is not only a great pleasure, but is a valuable means both of achieving expanded self-awareness and of developing his ability to interrelate with others. With Rolls: 1971, Third One Year Movie – 1972 is the most effective culmination so far of Huot’s need to make interesting, beautiful film art without becoming inaccessible, a need which has dominated his development as a filmmaker since the late 1960s. It is also his most powerful attack on an attitude which seems to underlie a good deal of both commercial and independent filmmaking and film criticism, the attitude that highest goal of filmmaking is the production of bodies of work which attest to the fact that their makers – film artists, auteur directors – have achieved the highest aesthetic professional status, and, by virtue of their ability to do things that their viewers feel they cannot, can rightfully command the respect, even awe, which are the prerogatives of superstardom. For Huot, film at its best would seem to be the production of films which cannot only provide viewers with an expanded awareness of some of the lifestyles which are open to them, but which can awaken in those who see the films the desire and confidence to participate actively in the making of their own art. Third One Year Movie – 1972 is a truly liberating film which implies that filmmaking needs to be no more mysterious, no more impossible for us than meaningful sexual interaction, sensitivity to our natural environment, the ability to provide ourselves with food and drink, or any of the other essential activities the film presents. It warns us by example of how much we’ll be missing – both in our art experiences and in other sectors of our lives – if we allow elitist assumptions about human needs and abilities to dissuade us from developing our own creative material.

Since Third One Year Movie – 1972, Huot has finished two diary films: Diary Film #4 – 1973 and Diary 1974-75. The first of these includes some lovely imagery and some interesting users of positive and negative color, but fails to create the intimacy between filmmaker and viewer which makes previous films so powerful. I have discussed Diary 1974-75 elsewhere. It’s a very interesting film, which grows increasingly impressive with each screening. The footage, most of it informal, was shot over a two-year period and edited during summer, 1978. Huot’s ease with the camera in Diary 1974-75 creates a continuous rush of experience. Friends, lovers, children, pets, landscapes hurtle through the camera’s field of vision, sometimes hovering long enough for us to identify them, but always moving too quickly for any sustained examination. At times the speed with which Huot’s camera passes across his world is rather frustrating. This is particularly the case when we are presented only a brief moment with particularly lovely imagery: the blue translucence of winter light refracted through a frosty window, a deep red wine color negative shot of some cows in a distant field, so many others. While the filmmaker may be moving more quickly than is comfortable for us, however, he seems to be enjoying every minute. In fact, the film seems to suggest that the pleasure and joy experience has to offer is, to a large extent, a function of its evanescence. It is as though Huot is afraid to stay too long, even with the most subtly beautiful images, for fear that he will filmically reduce them to boredom. Huot’s informality with the camera is reconfirmed by his editing the film in a more intuitive way than in previous diaries, and by his free use of a wide variety of filmic materials and processes. Within a brief sequence we may see imagery in a faded black and white, in color negative, in color, in black and white negative, in black and white positive with holes punched through the celluloid, in forward slow motion, in erratically pixilated fast motion, and photographed through or into transparent, translucent and reflective surfaces. Huot’s eclectic style tends to free us from preconceived assumptions about how various modes of presentation “should be used.” All kinds of presentation became equally valid, equally capable of capturing interesting imagery.

During the past five years Huot has also continued to be interested in other areas of the visual arts. During the mid-seventies he completed dozens of giant diary paintings, many of which have interesting relationships to the diary films. Shows of these paintings were organized at S.U.N.Y. at Albany in 1976 and at Utica College in 1979. More recently, Huot has turned his attention to “propaganda art,” formally powerful statements of his personal and political concerns. He has also made several hours of interesting videotapes. In my view, however, his most exciting new direction is his growing interest in Super-8 and Super-8 sound film. He is presently editing Super-8 footage of various kinds into new diaries; what I have seen of this material has been as impressive as his best 16mm work. Predictions are difficult, but given the combination of Huot’s independence and his obvious abilities and energy, almost anything seems possible. What is most clear at this point, perhaps, is that those of us interested in recent developments in avant-garde film already have more catching up to do than we may like to admit.

Scott MacDonald

Professor Emeritus

Utica College of Syracuse University

Scott MacDonald has written on avant-garde film for QRFS, Film Quarterly, Film Culture, Afterimage, and many other journals.