ROBERT HUOT – THE ART OF CONTEXT – 1969-1990

Originally published in ART PRESS – HORS-SÉRIE NUMÉRO 17 1996

69/96, Avant-Gardes et fin de siècle

First I have to open the window of time wider. When I think of the issues of art I must go back to 50’s and the days of 10th Street in N.Y.C. I was a young man infatuated with the life of an artist, hanging out with the 10th Street artists—closing the Cedar Bar—talking all night about art and politics—being a rebel yet part of a cause,what I saw then as an intoxicating way of life—bohemian—radical—far different from my father’s six days a week of enslavement. The New York School was in its hey-day and I was a small part of it. I went to every show, every opening and every party. Soon I knew everyone (the art world was smaller then). I worked in my studio 14 hours a day—made more paintings than anyone I knew—held down a full time job. I didn’t sleep much—just worked and partied. For about a month each year I’d collapse, then build myself up for the next stretch of art and madness. It was great. I was young—I had no one to worry about but me and I didn’t worry much about me—I was an artist, period.

So I entered my art life with a kind of religious fervor (though most secular). I went rapidly from “apprentice” to “journeyman” and began, along with many others, to develop a style to rival abstract expressionism—what was soon to be called “minimal art.”

Minimal art from my point of view was a style of efficiency—direct—color, shape, size, location, surface and light—what you see is what you get. A reaction to the “automatic writing,” the idiosyncratic nature of the then dominant style of abstract expressionism. We hoped to present the reality of the elements of art as a language that spoke directly to the viewer. These were not new ideas, but they seemed fresh and necessary in the seeming muck of the moment.

Minimal art from my point of view was a style of efficiency—direct—color, shape, size, location, surface and light—what you see is what you get. A reaction to the “automatic writing,” the idiosyncratic nature of the then dominant style of abstract expressionism. We hoped to present the reality of the elements of art as a language that spoke directly to the viewer. These were not new ideas, but they seemed fresh and necessary in the seeming muck of the moment.

The context of my entry into the world of art was affected by my friends and teachers. After serving the U.S. Army for two years (1958-60) I studied with artists Fritz Bultman and George Sugarman. At the same time I met Carl Andre, Bob Barry, Hollis Frampton, Bob Morris, Doug Ohlson, and later Twyla Tharp. We were all starting our art lives and shared the fever. Some of us also collaborated on a variety of projects.

My “Hard-edge,” “minimal” paintings were receiving a good reception from the critical and gallery communities. I was showing with Stephen Radich, then Paula Cooper in New York, Müller in Germany and Ziegler in Switzerland. I was “successful,” but uncomfortable. The Viet Nam War was calling into question my whole way of life. What was the function of my art? What was my role as an artist, teacher and intellectual? Was I simply going to go on with business as usual or take some kind of action?

My “Hard-edge,” “minimal” paintings were receiving a good reception from the critical and gallery communities. I was showing with Stephen Radich, then Paula Cooper in New York, Müller in Germany and Ziegler in Switzerland. I was “successful,” but uncomfortable. The Viet Nam War was calling into question my whole way of life. What was the function of my art? What was my role as an artist, teacher and intellectual? Was I simply going to go on with business as usual or take some kind of action?

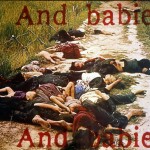

Not only was the Viet Nam War affecting our minds and lives, but the Civil Rights Movement was reshaping our world . We participated in anti-war and civil rights demonstrations. We formed organizations like the Art Workers Coalition (I was a founding member) and took a variety of actions, producing the Mai Lai Poster and demonstrating against the war and for greater participation of women and African-Americans in the art establishment. All of this affected our art and our sense of ourselves.

By the late Sixties I had become more and more involved with filmmaking and I had stopped making “regular paintings” (paintings on stretchers that could be transported and sold in galleries). My art became more and more “dematerialized” or “conceptual” and this transformation had strong political implications. By not making regular art commodities, I felt I was helping destabilize the art establishment (I had withdrawn from the galleries I’d been associated with). I was saying NO to art as usual. I felt artists had to take control of their art and not allow the “power elite” of the art world to control it and do with it as they wished. It seemed (and seems) to me that art in general serves the interest of the ruling class and for me (a member of the artisan class) this was and is unacceptable. So I “dropped-out” and became involved in an “alternate lifestyle.”

By the late Sixties I had become more and more involved with filmmaking and I had stopped making “regular paintings” (paintings on stretchers that could be transported and sold in galleries). My art became more and more “dematerialized” or “conceptual” and this transformation had strong political implications. By not making regular art commodities, I felt I was helping destabilize the art establishment (I had withdrawn from the galleries I’d been associated with). I was saying NO to art as usual. I felt artists had to take control of their art and not allow the “power elite” of the art world to control it and do with it as they wished. It seemed (and seems) to me that art in general serves the interest of the ruling class and for me (a member of the artisan class) this was and is unacceptable. So I “dropped-out” and became involved in an “alternate lifestyle.”

In 1969 I put a down payment on an old farm in upstate New York and on a cold January we moved in. At this time Twyla Tharp and I were married. We soon had our son Jesse. Farm and family had a profound effect on my life. I tried as much as possible to be self sufficient—live off the land, garden and hunt. After being so involved in the art world both as a gallery artist and an activist, this something entirely new for me. After producing some of the most extreme, dematerialized, distilled and almost invisible art in the late Sixties, in January 1970 I began a film diary.

In 1969 I put a down payment on an old farm in upstate New York and on a cold January we moved in. At this time Twyla Tharp and I were married. We soon had our son Jesse. Farm and family had a profound effect on my life. I tried as much as possible to be self sufficient—live off the land, garden and hunt. After being so involved in the art world both as a gallery artist and an activist, this something entirely new for me. After producing some of the most extreme, dematerialized, distilled and almost invisible art in the late Sixties, in January 1970 I began a film diary.

I had been working with film since 1966 (Hollis Frampton shared his editing bench with me). My early films were minimal (made from leader and found footage). The diary films were documents of everyday life—work and play—not in anyway adjusted aesthetically: when the camera was set up and turned on, what ever happened, happened. When these diaries were begun I had no intention of

showing them publicly. They were made simply as a tool of observation. Yet, as open and unpreconceived as they may have been, they still existed in an aesthetic context. I could not free myself completely–I was in a sense a victim of my history. The diaries were a kind of meta-art existing in a space somewhere outside of both movies and paintings, yet somehow connected. In March 1970 I began a series of diary paintings. They too were made as a tool to help me see again, with no intention of public exhibition. I hoped to live and work as much as possible outside the confines of society as I had known it.

showing them publicly. They were made simply as a tool of observation. Yet, as open and unpreconceived as they may have been, they still existed in an aesthetic context. I could not free myself completely–I was in a sense a victim of my history. The diaries were a kind of meta-art existing in a space somewhere outside of both movies and paintings, yet somehow connected. In March 1970 I began a series of diary paintings. They too were made as a tool to help me see again, with no intention of public exhibition. I hoped to live and work as much as possible outside the confines of society as I had known it.

Paradoxically my retreat from the metropolis to rural life (a radical act) brought me to a reaffirmation of many aspects of traditional values. I began to re-examine my whole relationship to life. Family, teaching and the environment became my preoccupations. I

eschewed the traditional art world. I avoided all galleries and museums, except for alternate and noncommercial spaces. Slowly the impact of my choices began to effect my art in a concrete way. The diary films became more and more a celebration of “nature.” As my awareness of my/our impact on the environment grew, I felt compelled to make my art and life reflect that awareness.

eschewed the traditional art world. I avoided all galleries and museums, except for alternate and noncommercial spaces. Slowly the impact of my choices began to effect my art in a concrete way. The diary films became more and more a celebration of “nature.” As my awareness of my/our impact on the environment grew, I felt compelled to make my art and life reflect that awareness.

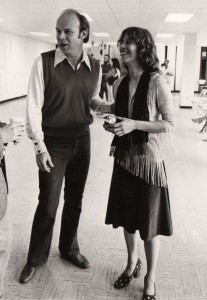

At this time my marriage with Twyla ended. This threw me into a state of reckless depression. Drugs and womanizing were my life. But, soon two people entered my life who put me back on track. Carol Kinne and Klaus Stoscheck gave me the friendship and direction that I needed.

Carol was also teaching in the art department at Hunter. Our friendship developed into a love relationship that lasts to this moment. Klaus had devoted himself to the study of Native American Cultures and ecologically progressive forms of  farming and gardening.

farming and gardening.  They both came to stay at the farm and we three began together and separately to embark on actions that would profoundly affect our lives.

They both came to stay at the farm and we three began together and separately to embark on actions that would profoundly affect our lives.

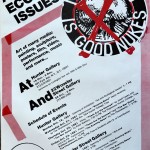

With a tiny inheritance from her mother, Carol bought a small farm nearby. We worked together on a variety of farm and art projects and we continue to do so. We traveled together with a group of artists and writers to China in 1977. On our return we presented a multi-media show including a China Diary composed of film, slides, taped music and live commentary. Carol has been a major contributor to my film activities both in the diaries and a series of short works produced in the late 1970s. Our next major project was a series of anti-nuke posters that appeared in the New York subways. This led us to mount our first “environmental art” exhibition in 1981.

Klaus Stoscheck had begun as an art and anthropology student at HunterCollege. He studied with both Carol and me. While he lived  with us at the farm we started a garden, which he supervised,

with us at the farm we started a garden, which he supervised,  using raised beds and intensive gardening techniques he developed. This led soon to an organic farm in Van Etten, New York. Klaus and his mother purchased a farm on the Kaiyutah Creek in southwestern New YorkState. They were soon joined by his brother, two sisters and a group of friends. They formed a coop which became a model for all those who came in contact with their adventure. Klaus took the name Kaiyutah Clouds and worked first with the Akwisasni in Canada and then went south to Guatemala to aid the Mayas after the 1976 earthquake. He spent the next four years in Guatemala working with the Cakchiquel Maya, making brief trips to the U.S. to raise money to aid in the formation of agricultural coops. In October 1980 he was murdered by a government death squad for his progressive activities. This led us to produce a film called KAI as a memorial to this fine young man. KAI was completed in 1989.

using raised beds and intensive gardening techniques he developed. This led soon to an organic farm in Van Etten, New York. Klaus and his mother purchased a farm on the Kaiyutah Creek in southwestern New YorkState. They were soon joined by his brother, two sisters and a group of friends. They formed a coop which became a model for all those who came in contact with their adventure. Klaus took the name Kaiyutah Clouds and worked first with the Akwisasni in Canada and then went south to Guatemala to aid the Mayas after the 1976 earthquake. He spent the next four years in Guatemala working with the Cakchiquel Maya, making brief trips to the U.S. to raise money to aid in the formation of agricultural coops. In October 1980 he was murdered by a government death squad for his progressive activities. This led us to produce a film called KAI as a memorial to this fine young man. KAI was completed in 1989.

In late 1980 Keith Aoki, Tim Grajek and I formed the Chameleons, a music and performance group. We have been working with Jeff Bruner, Hank Stahler, Carol Kinne and many others to produce songs, performances pieces, audio and video tapes, often with a strongly political direction. We continue the association today.

In late 1980 Keith Aoki, Tim Grajek and I formed the Chameleons, a music and performance group. We have been working with Jeff Bruner, Hank Stahler, Carol Kinne and many others to produce songs, performances pieces, audio and video tapes, often with a strongly political direction. We continue the association today.

What I call “the context of art/the art of context” has since 1969 been the richest period of my life. I have managed to produce art that reflects the changing contexts of my view of the world. I wished to try everything and to a degree have done so. I tried to put myself in a position to make only what I wanted to make. Fortunately, I had a good job, and have an adequate retirement, which allows me to be my own patron so to speak. For many years, I was able to live as an “educrat” with relative freedom, teaching in the progressive atmosphere of the New York City Public University System. I feel most fortunate. My son Jesse is healthy and happy. He has begun working as production assistant for an excellent producer. My wife Carol and I are in good health and have enough to do for two life times each.

With the joy there is the sadness of maturity. I remember my naïveté—the simplicity of views—my dreams. I believed art could change the world and I continue to hope it can make a contribution. Art has certainly provided a way (in the Zen sense) for me to structure my energies. But I guess I feel we progressive artists lost a chance during my lifetime to make a greater impact. In recent years by not doing the day to day mundane business of politics we allowed the “religious” right to take power. In the vacuum we left. We are faced with censorship not equaled since the McCarthy era. Though women, African-Americans and others have assumed roles of power, the same good old boy net-work calls the shots. There is no energy policy, public schools decay, the inner cities collapse, racism and violence increase and yet our only mobilization is a war machine to fill the vacuum of vision in domestic and foreign policy. Is it any wonder we all feel a sense of sadness and helplessness? Isn’t it time to mobilize art again? Isn’t it time to release all the powers of human creativity to live symbiotically in this solar system?

On my fifty fifth birthday, the 16th day of September 1990, Columbus, New York.

Robert Huot

{Couldn’t this last line be: “On my 78th birthday, the 16th of September, 2013, Columbus, New York. — edit/comment SM}