HUOT’S SEARCHING IMAGINATION

The diary paintings unfurl like a torrential jazz riff of experience, darting and leaping from point to point but rushing forward in a broad gush of life and energy. They are a giant record of quotidian and art historical events plucked and placed within a broad time and space structure under game rules that evolved from the earliest of what might be termed scale exercises to the most recent lyrical explorations.

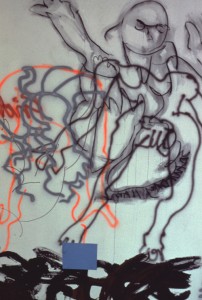

The size of these huge canvases ranges from sixty to ninety feet and provides almost a landscape of painterly design. They are intended to be displayed in a variety of ways, and wrap around horizontal environments, or mammoth banners to be read vertically or floor pieces to be paced off like an esthetic fairway. In only one case has the scroll design been abandoned in favor of “leaves” and that is Number 47, where its twenty-six elements reveal an alphabet of concerns, touching upon figure drawing, politics, sex and encyclopedic fascination of a mail order catalogue. One has the sense of impatience and perhaps even anger as operating concerns driving the formation of the “pages’ of this particular journal of experience, as Huot comments upon events. But to appreciate its diversity one should consider some of the earliest paintings.

One of the first diaries, Number 3, is a record of paint manipulation in starker terms. The palette is restricted to black, white, gold, and dull yellow and the space allotted to each day’s exploration is ruled strictly with a carpenter’s chalk line. There are seventeen panels and seventeen encounters, the last a simple dating. Jars of left over paint stand at the foot of the canvas like the exhausted tools they are. The first day is a giant splatter and drip of yellow, a gesture of heedless necessity. Something had to be done to get started. Subsequent days find black pigment being stroked, smeared, spotted and brushed on in a variety of patterns like a musical rhythm with Huot an accompanying melody. Toward the end of the first week, a pristine path of gold is rolled up the canvas with diminishing intensity. On the seventh, a whimsical impulse finds the artist affixing his billed cap to the surface whose color links us referentially to the first day and its devil-make-care scattering of paint. On until the end though, there is a feeling of necessary probing, a self-assumed task to greet and work on a certain expanse of canvas within determined limits. Exploration predominates rather than resolution, means rather than ends, a feeling of finger strengthening exercises more than a freely swinging and open ended development of themes.

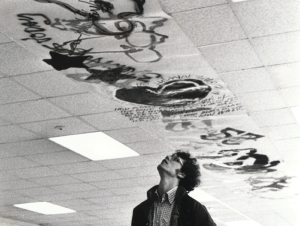

The diaries began in May of 1971 with some canvas rolls that remained after Huot abandoned stretcher and canvas in 1968 to engage in what he considered “egoless” art. The works produced in those years were of the most transitory kind and consisted, to a great extent, of artistic acts made in public or private spaces that were celebrations of the particular area. Many of these organizing and illustrative pieces are no longer in existence and can be experienced only in documentary photographs. They were commentaries on the properties of rooms emphasizing characteristic features with a bit of paint, a row of nails, some phosphorescent tape or at times judiciously places lights which showed surface texture through shadow patterns. In all cases they were not transportable or transaction prone, thus existing outside of the world of commerce and immediately became the property of others who lived in or owned the host areas.

They demonstrated a subservience to the givens of a particular space, accepting its idiosyncrasies of construction and attempting to illuminate its character with a great economy of means. The space was to be enhanced and not to be dominated, to be cherished for what it was and not what one could make it over into. It reflected an attitude of cultivated passivity and showed a desire for chance enrichment that dominated the artist’s thinking during the two and a half years in which he devoted much energy to film making and the practical politics of art and artist’s place in the world of possession and display that uneasily links galleries, museums, artists and the public.

During this time the prototype of the diaries began to emerge as he exposed a hundred feet of film each week, freely taking those things that caught his attention. The accumulation of this footage was a pictorial journal that developed within the strict format of a set amount of film shot during each seven day period. Again Huot refrained from imposing any special order on his experience forcing it into any sequence other than its own suitable time structure. As he had done with space in the location pieces, taking the given ground for what it was, where it was; he now did with time, accepting experience as it transpired and simply recording it. Like a period of meditation, it refreshed his approach to the more traditional painterly means.

Looking at the earlier diaries, Number 10 is the first to show all of the elements which would be orchestrated in the series. For the first time there were combined writing, dating, splashing and sprinkling of glitter dust on the surface. The writing which at times conforms to elaborate spirals or loop formations is frequently difficult to read but always records something of the artist’s concerns whether painterly or personal. At other times it is as straight-forward as a copybook exercise. The addition of glitter dust has a kind of funky glamour, almost in a theatrical sense of performance costuming.

Emerging from the series of paintings however there is an overriding concern with the craft of painting and restless quoting from various contemporary styles. A female nude at one time has a picassoid look and at another moment is rendered to remind us of de Kooning’s motor drive. Clyfford Still’s flickering brush is suggested as is the precision of a Mondrain grid in other places. Throughout his career, Huot has evolved from one mode of expression to another driven by a dissatisfaction with set solutions and forcing himself to seek new resolutions regarding the problems of structure and improvisation.

In Number 41 there is a giant countdown of numbers leading to a blast off image of a rocket about to lift from its pad. On the way down one notices the “9” woven out of a line that is reminiscent of Pollock and later on the “5” carries a witty observation to the Jackson Five, a rock group to be sure, but also Pollock’s first name. The use of the cartoon as a simplified and exaggerated drawing tool reveals an essay at lively draughtmanship in a way divorced from lyrical color and its judicious use, though one is made aware of a steadily brightening palette.

The diaries are a record of speed dominated by time and a searching imagination probing daily events, personal concerns and art history for pictorial sense. The present works stand as milestones of a continual concern with formal structure and spontaneous gesture. In the past the field has often functioned as a passive object onto which was cast the rapid action of very brushy energy. Then again the field has been a broad dominant entity upon which keenly plotted and hard edged form has made a discreet but bold imprint. The play of the gesture and structure has been the esthetic tug-of-war that was at one time resolved by the creation of huge grid founded paintings and at another earlier time by the speedy slashing of expressionist color with less formal underpinning.

A selection of earlier work, all of an infinitely smaller scale, provides a survey of past solutions. Starting with an early collage, there is a concern with texture, in this case burlap, newspaper, paper with a unifying gesture of black ink that has developed into the use of the surface in a sculptured fashion. In one later, notable example the painterly blue field exists as a background for a built up wooden cross rising from the surface in ascending steps like determined miniature staircases. At times the energy of the gesture has been stilled into hard edged forms which exert a bulky grace and overall there is a feeling of large scale. Humorous touches appear as subtly different colors or shapes confront one another and toy with the viewer’s perception. But these are abstract witticisms compared to the lusty laughter one derives from the diaries where personality is allowed its raw sway. The activity of human encounter has burst from its cool confinement.

It was inevitable, given the format of the works that one, Number 48, would include the inscription “Dear diary I’ve got a confession to make..” It is also ironically enough an entry which is penned at the conclusion of the series rather than at the beginning. Under the original rules, the entries were made for a specified time period and in this one there is a feeling of a New Year’s party toasting the end of one time and the beginning of another. The colors are bright, the shapes are whimsical and the explosiveness of celebration bursts out of the canvas. The work continues the resume of styles that is one of the features of the collection but also points to the joining of drawing and painting again which is one of the deep motifs of the series.

Subsequent paintings use the large format but are not a record of daily experience and the first of the new begins with loosely interpreted anatomical drawings selected from a medical text but rendered in black line. Luscious areas of paint are applied touching on or supporting the drawings and the synthesis of color and line begins again. The structure and the painterly gesture edge up independently to one another’s borders, each having declared its independence and now will continue their discourse on the expanded plain of these great scrolls. Like those giant banners that decorated medieval halls announcing the rank and pedigree of the bearer, these mammoth strips attest to the risk, the accomplishment and the history of their evolving.

Don McDonagh

Don McDonagh wrote an art chronicle to the “Financial Times” of London for five years. He is currently dance critic for the New York Times.